-

Stage 2 survey trenches

Bernice Warren Center for Archaeological Research excavation in ex-parking lot on Mill.

-

Archaeologists at work

C.A.R. archaeologist and geoarchaeologist at work, Summer 2024

-

C.A.R. excavation, tan pits

Trench with remnants of Jessup's tanning yard

-

C.A.R. trench near Campbell and Mill

Stone and brick foundations of a building (perhaps Springfield Concrete, Hide and Junk)

History of Brick City and Jordan Creek Valley

Section Contents, Part One

- 'Dude, Where’s My Parking Lot?’

- The Earliest Peoples; The Osage & the Kickapoo

- Early Euro-American & African-American Settlement in the 19th century

- Industry and Artisans

- The Springfield Manufacturing Company

- ‘Boonville Hill’ Infrastructure & Jordan Creek Floods

- Railroad Arrives & the Wagon Company Moves On

- Industry and Commerce at the Turn of the Century

CONTINUE TO PART TWO: THE TWENTIETH CENTURY

'Dude, Where's My Parking Lot?'

Students, faculty, and staff returning to Missouri State of Art and Design's home at Brick City north of Springfield's Park Central Square in Fall 2024 will definitely notice that something strange is going on across Mill Street between Boonville and Campbell Streets, and as far as Main Street to the west. The most immediately obvious change is the closure—and, in time, total disappearance—of the parking lot between Mill and Water Streets. Over the course of the 2024-25 academic year and beyond this transformation will continue as the parking lot transforms into park land.

Many who are new to Springfield's history and hydrology may be unaware that this section of our urban brick, concrete, and asphalt environment in fact lies directly over the remains of a portion of Wilson's Creek—the same creek that runs through the Civil War battle site southwest of town—although they may be aware of its longtime nickname, Jordan Creek, on account of the names of some of the buildings in the neighborhood.

The ‘Renew Jordan Creek Project’ underway will daylight approximately 1,200 feet of creek between Boonville and Main and create a mixed-use park that runs along the creek that can serve as an open space for the community. As the Renew Jordan Creek project plan explains, ‘the Project represents the first phase of a comprehensive planning effort and other large-scale improvements in the downtown area, largely focused on flood reduction and water quality improvement.’ The new path of the Jordan as a ‘natural riparian corridor’—an ecosystem of wetlands and aquatic plantings—will serve to temper the effects of flash flooding (welcome news to longer-term students, staff, and faculty who have experienced some of these surprises) and improve quality of the water in the Jordan and provide enhanced habitat for wildlife. There will be some structural changes: A new 55-foot single-span bridge over Campbell will be adjusted to the new waterways and will replace the old nineteenth-century stone arch bridge which, while lovely, is aging precariously and is only visible from within the underground trench; the old building that some will remember fairly recently as housing the Idea-X Factory, while also of some historical note for its midcentury industrial style, will also be thoroughly documented and razed as part of the project.

The parking lots across Mill from Brick City were closed to use in late May, 2024, and over the month of June archaeologists and geologists led by a team from the Center for Archaeological Research at MSU dug a half-dozen exploratory trenches between the east edge of the parking lot near Boonville to just east of Main behind the Hotel of Terror. A range of artifacts uncovered in this survey will be catalogued: the majority of them serve as evidence of the late nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century height of activity along Boonville and Campbell—remains of the old tanning pits, the foundations of a building on the east side of Campbell (perhaps the Springfield Concrete, Hide and Junk Company), and great amounts of manufactured detritus like glass bottles, broken ceramics, bricks, battery cores, and barrels of nails. Further west, toward Main, greater evidence of pre-nineteenth-century presence was found: in particular, some 'PPK' artefacts (projectile points or knives, in practice very difficult to differentiate) have been unearthed that still possessed certain 'diagnostic' features that will suggest a more specific age and cultural origin for these items.

As we await the archaeologists' specific findings that will shed light on the very earliest history of the neighborhood, a survey of the nineteenth- and twentieth-century history of this section of the Jordan Creek Valley provides a sense of the range of roles that the neighborhood and the creek has played in the larger story of Springfield. These insights into our location reveal its artistic, artisanal, and industrial hertiage—a story that we now contribute to—and explain the complicated origins of the buildings that the Art and Design Department inhabits today, answering a lot of questions about this place (including 'what is that thing in the middle of the ceiling of Brick 4?,' 'Brick...2?,' and 'why is the only actual hill in Springfield exactly where I have to bike to the main campus?').

The Earliest Peoples, and the Osage and the Kickapoo

Before the late eighteenth-century French explorers arrived, what would become the state of Missouri was the home of the Dhegiha-speaking Osage, the Chiwere-Siouan Missouria, and the Illiniwek Confederacy of the Cahokia, Kaskaskia, Michigamea, Peoria, and Tamaroa peoples. By the end of the eighteenth century there was already significant movement westward across the Mississippi of groups of Delaware and Shawnee who were granted lands in southeastern Missouri by the Spanish in 1793. After the region became part of the United States with the 1803 Louisiana Purchase, the government’s policies of forced removal of native groups westward, such as the 1818 Treaty of St. Mary’s, displaced the Delaware, Kickapoo, Peoria, Wea, Piankeshaw, and Shawnee to southwest Missouri by 1821. These groups settled in villages along the James River and up Wilson’s and Finley Creeks: in 1828 a Delaware village was located just south of what is now Springfield at Delaware Town (aka Anderson’s Village), and there may have been smaller settlements near Rountree Spring. The immediate area of Springfield was part of Osage hunting lands, but no definitive Osage settlements have yet been located; at the same time, Kickapoo groups did frequently settle in these same lands, including in 1812 a Kickapoo settlement near a spring close to what is now South and Madison. In the 1830s the Cherokee would also be compelled west along the Trail of Tears, passing through Greene County and what would become Springfield. In any case, one of the first acts of the newly-formed Missouri General Assembly in 1821 was to negate all native land claims in the state, and with the Treaty of Council Camp (1829), the Delaware were compelled to give up their lands and relocate to eastern Kansas, and by 1832 the Kickapoo lost the last native land in Missouri and were likewise relocated to eastern Kansas and Oklahoma (although a formal legal agreement was reached, some of the Osage offered firm resistance throughout the 1830s). 1

Early Euro-American and African-American Settlement in the nineteenth Century

While earlier European American settlers had arrived several years earlier in Greene County, first described in writing by Henry Rowe Schoolcraft in 1818–1819, the origins of the city of Springfield lie not far away from what is now Brick City. According to tradition, John Polk Campbell and his brother Madison Campbell arrived in then-rural southwest Missouri from Tennessee in 1829. Initially camping at Delaware Town, a Kickapoo guide led them along what would eventually be known as Wilson’s Creek to Kickapoo prairie—along the edges of which were small Kickapoo settlements—with its natural resources, and numerous springs including a spring or natural well (at roughly the location of Founders Park on what is now Water Street). John carved his name into a nearby ash tree, and returned to Tennessee to retrieve his family. Local tradition holds that a Kickapoo leader gifted Campbell the land as a reward for medical treatment of a family member; this part of the story may be a comforting fiction, and the US government, however, further removed the Kickapoo westward in 1831. Meanwhile, William Fulbright, who knew Campbell from Tennessee and was living in Rolla, also moved to the area (building that family’s cabin in the vicinity of West College and Newton). Fulbright’s brother-in-law, A. J. Burnett, found Campbell’s stack of lumber and, thinking it abandoned, built a cabin near the site—what is now the northeast corner of Olive and Boonville—in 1830. On his return, John Polk Campbell showed Burnett his initials on the ash tree near the spring that marked his prior claim to the land, and Burnett duly turned over the cabin.2

The community started by both families and a handful of others expanded quickly. In 1831 the first store was opened—at the location of the later Frisco building—by Junius Campbell, John Campbell's brother, and in 1834 a post office was opened—Junius Campbell serving as the first postmaster; in the same year the first jail—a double log structure—was built on the east side of Boonville between the square and branch of Wilson’s creek (the ‘Calaboose’ was built only in 1870). In 1836 the first timber frame houses were built as well as the first brick chimneys, using homemade bricks. In 1833 Greene County was officially designated, and the earliest court proceedings were held at John Campbell’s home. In 1837 the county designated $100 out of the road and canal fund to build a bridge across ‘the town branch, north of the public square’—that is, the Jordan Creek stretch of Wilson’s Creek—the first such expenditure on a bridge by the county.3

-

Jordan Creek from east at Jefferson Street, 1932

Location, roughly, of E-Factory. Back of old Frank Smith Laundry visible. Image courtesy of the Springfield-Greene County Library District Postcards and Photographs Collection

-

Jordan Creek flooding, 1909

Image courtesy of the Springfield-Greene County Library District Postcards and Photographs Collection

-

View of creek at high water and town from Benton Avenue, 1932

Image courtesy of the Springfield-Greene County Library District Postcards and Photographs Collection

This section of town, in addition to early industry, was a center of life for the mid-nineteenth-century African-American community of Springfield, both the enslaved and the free populations. In 1841 permits were first granted to free African-Americans to live in the city, and until the rapid expansion of industry along the Jordan in the 1880s many Black residents lived in a portion of the Jordan Creek Valley nicknamed ‘Happy Hollow,’ roughly between the area of Boonville and Jefferson eastward to National.4 As Loring Bullard has reported in connection to the nickname of ‘Jordan’ for the stretch of Wilson’s Creek that passes through downtown Springfield, there was ‘an early African-American church, a yellow frame building, which used to sit near the banks of the Creek about where the corner of Jefferson and Phelps is today. So much baptizing was done at this spot that people began to refer to the creek, somewhat sarcastically, as the “Jordan.”’5 By 1868 the only two church buildings north of the Square served Black congregations: The Methodists at Wilson’s Creek Chapel and the Second Cumberland Presbyterians at Benton and Water (and the Second Baptist congregation who met there as well). Earlier in the century the Methodist congregation likely met in the woods near the creek, but in 1847 one of the members of the congregation, William Townsend, petitioned the man who enslaved him, William Townsend, for permission to build a church on the banks of the creek. The city granted permission for this structure in 1847, likely a log construction on the Jordan known as Wilson’s Creek Chapel.6 The congregation rebuilt with a frame building also in the neighborhood at Phelps and Jefferson, which served as a Sunday School for adults and then for all of the Black students of the city until Washington Avenue school was school built in 1872. Flooding in 1909 is reported to have washed away this building, and in 1911 the Methodists completed a brick church building at Benton and Tampa (formerly Pine Street) where it still serves, now known as Pitts Chapel after an early pastor.7

In time the expansion of the square’s commercial activity and industry on the creek would pressure many of the residents of Jordan Creek valley further north to other neighborhoods in the city. In the African-American history of Springfield, however, the early neighborhood featured in yet another notable way as the location of events in the struggle for emancipation, only recently excavated by archivists. In 1836 at the northwest corner of Olive and Boonville was the house of John Edwards: not much is known of him, but he appears to have been an abolitionist, and in 1836 his family seems to have housed Milly Sawyers. Sawyers had previously been enslaved here in Greene County by William Ivey, but in August of 1835—in her third attempt in court—she had been legally declared a free woman. On April 1, 1836, however, a mob showed up at Edwards’ house and dragged Sawyer out of the building and battered her. Several defendants were charged with the assault; among the mob were Lucius Rountree and then 24-year-old Junius Campbell (Junius was subsequently charged with lying under oath after denying that anything had happened that night). After this trial, Milly Sawyer disappears from the archival record, but this part of her story has fortunately been recovered.8

Industry and Artisans

It is in these first decades of the city’s development that we find the earliest indications of this neighborhood serving as a hub of artisanal and industrial activity, with its streets becoming primary commercial and manufacturing arteries as the city and business spread out from the square: Boonville the north-south street that led in the direction of Boonville, Missouri (then an important riverport and rail town), and Mill street receiving its name as, naturally, where the mills were located. The first hide tanning yard for the production of usable leather, run by Thomas Jessup, was constructed in Jordan valley south of Mill and west of Boonville, poorly documented but now verified by archaeological evidence.9 In 1858 the Butterfield Stage began to serve the city, contributing to a quickened expansion until interruption by the war: it brought mail and passengers, operating from a station and stables on the northeast corner of the square previously used by an early gunsmith in town, Jake Painter, whose shop moved to Olive and Patton) and lodging at Smith’s Tavern on the corner of Boonville on the square (now roughly the location of The Riksha).10 At the northeast corner of Phelps and Boonville, Captain Alfred M. Julian had a wool carding machine operated by ox- and horse-power, and Capt. E. B. Smith also ran a planing mill on the east side of Boonville.11 A blacksmith named Jenkins had a shop on the north side of the Jordan on Boonville at an early date.12 Charles Perkins established a carriage factory on Boonville street shortly after the end of the Civil War, and a blacksmith’s shop was operated by 1856 by Aaron Nutt, located ‘near Boonville street, near the old tan yard,’ and ‘at his old stand on the West side of Boonville street.’13 This was followed by William H. Lyman who ran a blacksmith shop at 202 Mill which remained in business for several decades: this was on the south side of Mill, across from what is now Brick 3 and 4: perhaps the same site as Nutt’s.14 The O. K. Flouring mill was built in the mid 1850s on west Mill by Allen Mitchell and John Caynor. A shoemaker named Jopes ran a shop on Boonville, and from 1858 Hancock Haden & Company ran a small tobacco factory to the west on Main Street. In the same year, 1858 Jared E. Smith built a planing and flouring mill on Boonville Street on north bank of the Jordan, perhaps the first use of steam power in southwest Missouri (the later site of Schmook’s Mill).15

In 1858 a Prussian immigrant, Charles Gottfried, opened a furniture and cabinetry shop on Boonville Street that remained in business until 1947: the latest construction of that building—built around 1890 and listed on the National Historic Register—today serves Carolla Gallery. At some point a foundry was operating at the site of Brick City 1, where in 1865 Holcomb and Thompson would rebuild and found the Springfield Iron Works.16 As of Christmas 1858, among these other institutions there was operating ‘one saloon, the latter institution being located beyond the “Dead Sea,”’ that is, Jordan Creek. The early 1860s, of course, saw the Civil War and a temporary pause for Springfield industry as troops occupied the town, the Battle of Wilson’s Creek and the Battle of Springfield were fought, and government business halted sporadically. The August 1861 Confederate occupation saw troops encamped on both sides of the Jordan, and in October the old brick courthouse on the square was burnt in a fire started by an unstable prisoner. With the end of aggressions Springfield began to grow more rapidly. In August of 1865 Holcomb & Thompson rebuilt the Springfield Iron Works foundry ‘over Jordan’ at Mill and Campbell, and expanded it in the following year to cast machinery and steam engines; Lyman’s blacksmith shop continued to operate across the street. The steam mill across Boonville was rebuilt and started up and a large brick yard began to operate on Mill.17

The brick yard was a necessity, as newer brick buildings were more resistant to fire than log or timber-framed constructions. In February of 1867, for example, fire started in an old wooden-framed grocery and agricultural implements store on the north side of the square; in its upper story was the Union Press newspaper office. From here fire spread to neighboring wooden buildings including the Union Hotel—one of oldest structures in the city—and other shops. A small house and a shoemaker’s shop were torn down as a fire break, but the fire spread as well to a saloon, a stable owned by the Stage Company, and northward to dry goods shops, warehouses, and a row of small houses on the alley (later Water Street) occupied by African-American families. The Press office only saved two cases of type, and what goods were salvaged from the various grocers were ransacked by looters. A decade later, a fire in Lyman’s old wooden-framed blacksmith shop on Mill likely started with live cinders left on the forge that spread to the walls and roof, but quick action saved the industries along Mill street.18 In time, H. T. Rand bought a Kennedy Dry Press Brick Machine and Schmook’s brickyard at the bridge on Boonville, where he set it up.19 Brick as a material was deemed noteworthy, suggesting a business’s success and stability.

[A map of town in 1863, during the Civil War, at https://www.springfield1863.org shows the few streets constructed by that time. The central square serves as the intersection of Boonville and College Streets, and the run of Fassnight creek and what will be the site of MSU main campus remains woods at the edge of town]

By the late 1860s, this neighborhood was, aside from the cotton mill further east on the creek, the principal industrial center, as papers of the time noted:

‘On or near this street are located nearly all the manufacturing establishment of our city. The street runs east and west, on the north side of Jordan, beginning at Boonville street and running parallell [sic] with that classic stream. Nearly at the head of Mill Street, on Boonville, is the Plaining and Flour Mill of Mr Schmook, near the corner is Lyman's blacksmith shop, a little further west Piper's shop, and beyond is foundry of Holcomb, Thompson & Co, and the extensive steam flour mill of A Mitchell and Co. A square north of the Foundry is the new Steam Plaining Mill of Knott & See.’20

The Foundry, on Mill Street at the site of what is now Brick City building 1, advertised ‘threshers, cider mills, cane mille, grain drills, etc.’21 A large advertisement for Schmook’s Steam Flouring Mill ‘at the lumber yard, opposite the mill, on Boonville,’ asserts that, ‘I can grind all the grain that may be brought to me,’ and that the owner also keeps ‘a general assortment of building material on hand, prepared to dress and match floors and siding, etc’: this site would eventually serve Queen City Mills, the Meyer Milling Company, and from 1928-2000 the MFA Milling Company, whose silos still stand prominent in the neighborhood, although the mill site itself is now the Jordan Valley Innovation Center.22 The Knott & See lumberyard would be succeeded at its location nearby by L. W. McLaughlin, and then by the Chicago Lumber Company, and by 1893 the Springfield Planing Mill & Lumber Company.23 The area between the square and the creek was also a dense mercantile and commercial center, lined with storefronts and artisans on both sides of Boonville. An early business in the area was the dry goods store of Victor Sommers, of one of the very first Jewish families in Springfield. On Boonville by 1868, the store moved into a larger, brick building on the west side of Boonville between the square and the creek in 1869 before it finally moved to the square itself.24

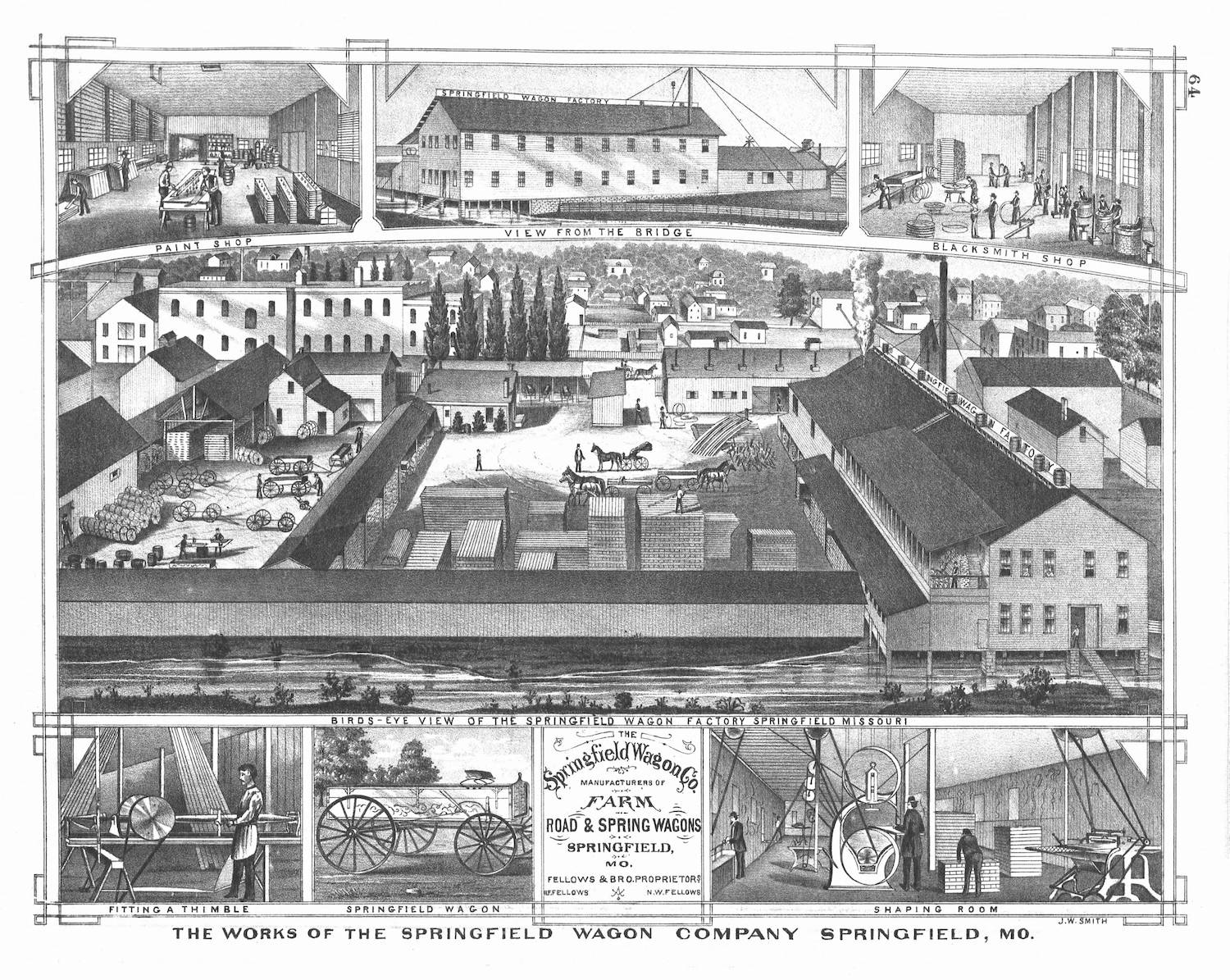

The Springfield Manufacturing Company and Springfield Wagon Factory

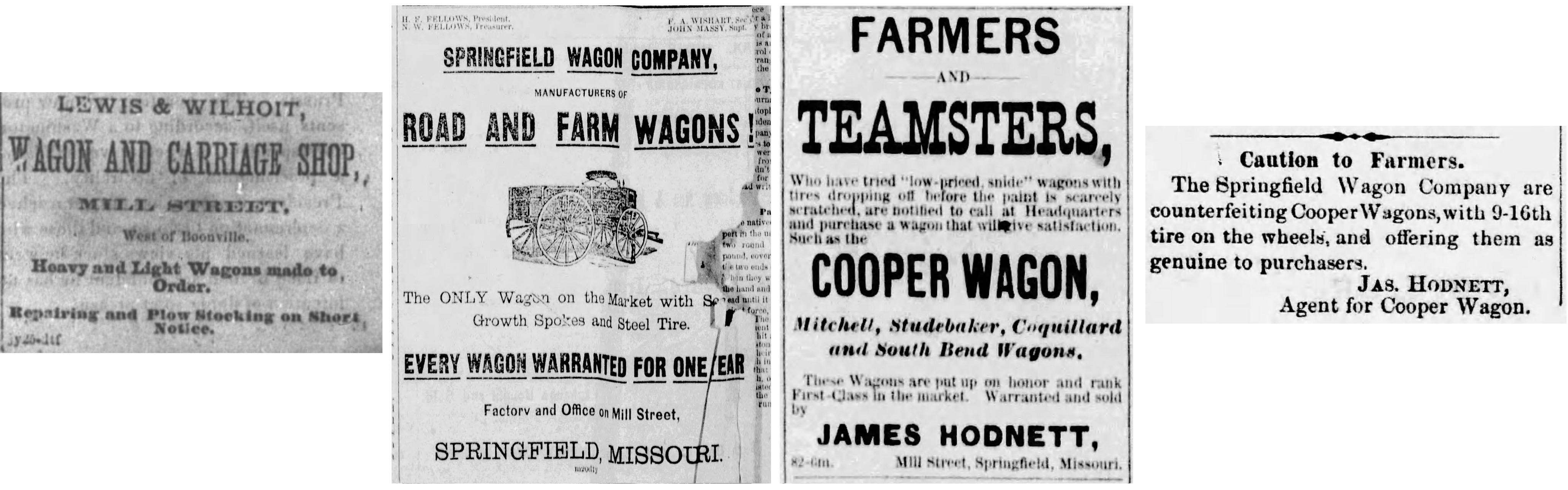

The most historically significant contributor to industry in the neighborhood, and southwest Missouri in general, was the first iteration of the Springfield Wagon Company. Initially the Lewis and Wilhoit Wagon and Carriage Shop, this was originally located on the large block between Boonville and Campbell, bounded by Mill on the north side (thus across from what is now Brick City, on the plot that was until recently parking and that will soon be park). An article of 1870 noted, ‘The manufacture of wagons in this city is growing steadily. Lewis and Wilhoit are rapidly increasing their business, and are now making wagons which can not be excelled. They also do all kinds of repairing. Their shop is on Mill Street, west of Boonville.’25 With the arrival of the railroad north of Springfield in 1871 and the construction of the first grain elevators, farm production had increased and the city government offered subsidies for new industry. In 1872 a collective of entrepreneurial stockholders acquired this same land to build wagons and plows as the Springfield Manufacturing Company under the leadership of Homer F. Fellows—who also owned the local telegraph, a general store, a furniture concern, and some plans for farming equipment—and Sempronius H. ‘Pony’ Boyd (among other things Springfield’s youngest mayor, Union Army veteran, US Representative, and Consul-General to Siam).26

A view of the Wagon Factory from An illustrated historical atlas map of Greene County, Mo, 1876 Philadelphia, PA : Brink, McDonough & Company, 1876): the 'view from the bridge' at top refers to the bridge over Boonville (there was not yet a bridge over Campbell); the large view is from the south across the creek around what is now the parking lot above Water Street; the blocky structure to the left in the background is what must be the Springfield Iron Works foundry, standing on what later would be the site of Brick City building 1.

Initial financial difficulties included a stock market crash in 1873, but their efficiency

increased with the addition of a blacksmith shop in 1874 and a kiln to finish air-dried

lumber. It seems that the owners perceived further financial trouble as marring the

company’s image, and in June, 1877 they received state approval to rebrand and reorganize

as the Springfield Wagon Company. In the following year they expanded at the site,

added a two-story paint shop and installed a new spoke-driving and wheel-rimming machine;

in this year 50 hands were employed there.27 In the same years, a competing wagon company was in operation just down Mill Street

between Campbell and Main. This shop, run by James Hodnett, produced the Planter Wagon

and distributed the Studebaker, South Bend, and Cooper wagons in Springfield (operating

until 1908). Lawsuits suggest that this was a bitter rivalry, as Hodnett sued Springfield

Wagon for stealing his wagon design, who countersued for slander; in the end both

suits were dismissed, but advertisements of the 1870s and early 80s testify to the

tone of the relationship, as do spicy accounts of squabbling city council meetings—gleefully

reported in the press in lurid detail—with Fellows as Mayor while Hodnett was a council

member.28

Initial financial difficulties included a stock market crash in 1873, but their efficiency

increased with the addition of a blacksmith shop in 1874 and a kiln to finish air-dried

lumber. It seems that the owners perceived further financial trouble as marring the

company’s image, and in June, 1877 they received state approval to rebrand and reorganize

as the Springfield Wagon Company. In the following year they expanded at the site,

added a two-story paint shop and installed a new spoke-driving and wheel-rimming machine;

in this year 50 hands were employed there.27 In the same years, a competing wagon company was in operation just down Mill Street

between Campbell and Main. This shop, run by James Hodnett, produced the Planter Wagon

and distributed the Studebaker, South Bend, and Cooper wagons in Springfield (operating

until 1908). Lawsuits suggest that this was a bitter rivalry, as Hodnett sued Springfield

Wagon for stealing his wagon design, who countersued for slander; in the end both

suits were dismissed, but advertisements of the 1870s and early 80s testify to the

tone of the relationship, as do spicy accounts of squabbling city council meetings—gleefully

reported in the press in lurid detail—with Fellows as Mayor while Hodnett was a council

member.28

‘Boonville Hill’ Infrastructure and the Jordan Creek Floods

The street between the square and the bridge over Boonville had been graded to some degree to reduce the steep slope.29 The pressure on the neighborhood to improve its bridges and roadways and to tame the creek increased with the explosion of activity at the Wagon Company, with much bickering in civic meetings and the press regarding street improvements with property owners on Campbell, like Hodnett, lobbying for that street to be opened to the south with a bridge, and property owners on Boonville, including the Wagon Company, instead wanting that street to be leveled more thoroughly with a substantial stone bridge over Jordan to replace the older structure. One petitioner at city council took the opportunity, ‘to draw glowing pictures of the horrors in store for future passengers down Boonville St. when the place now occupied by the bridge should be filled with grinning skulls of men untimely killed in passing over.’30

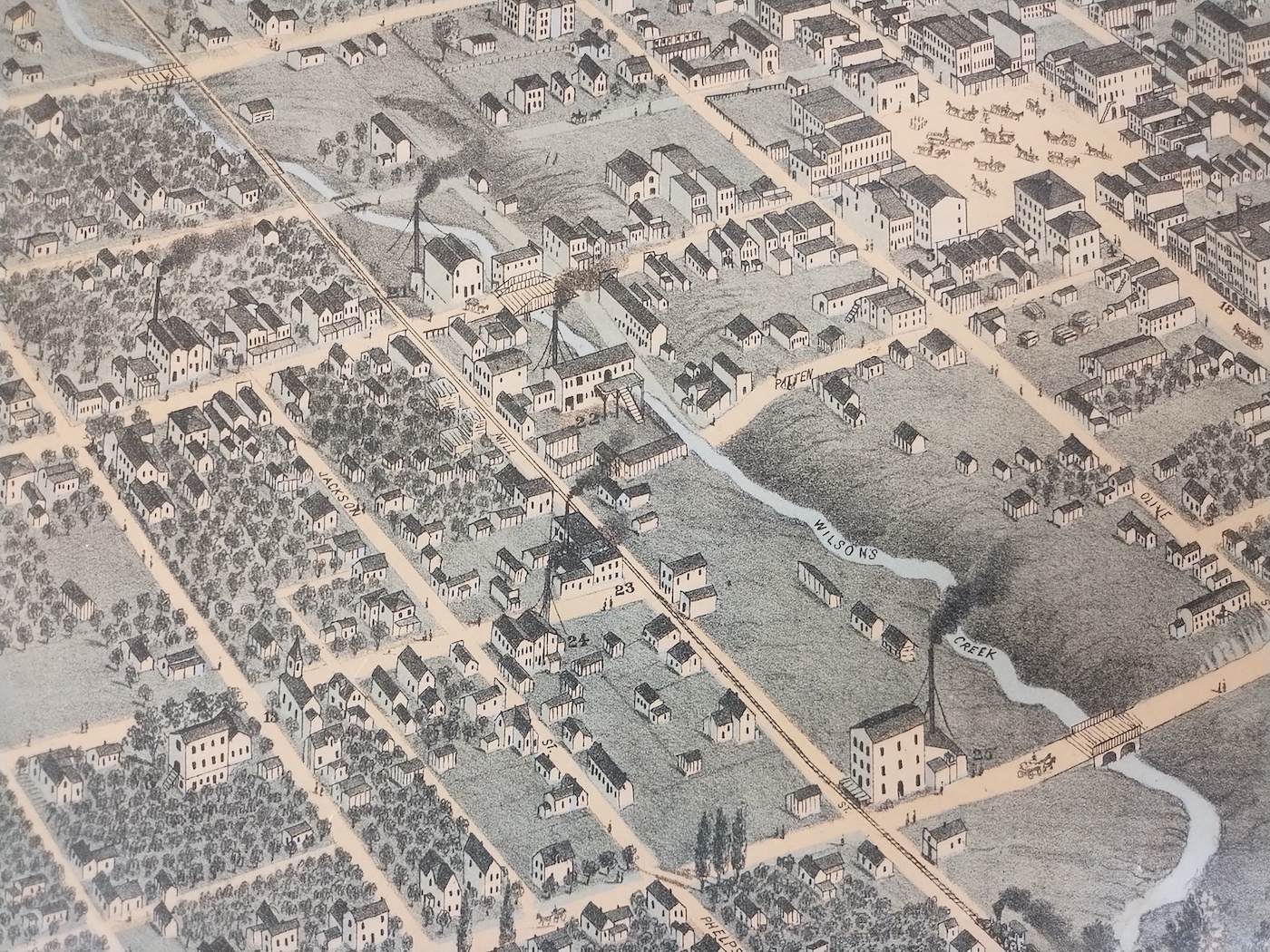

A lithograph depicting a ‘bird’s eye’ view of the city as it was in 1872 provides an impression of how Springfield had developed by that year. This neighborhood features prominently north of the square, with the mill at the old wooden bridge, the Wagon Company, and the Iron Works clearly depicted on the banks of the Jordan along Mill and Jackson (as this stretch of Phelps was still called): the south bank of Jordan Creek is precipitously steep in this area of the creek (as cyclists to Brick City today are well aware). Upstream to the east the cotton mill provided the only rival industry. The churches that served the local residents are also clear; the congregations on the north side of the square, with the exception of the new Catholic church, remain African-American. The area east of Boonville—east to Benton and Washington and north to Chestnut—looked very different, a residential neighborhood with now-renamed and lost streets like Vine, Pine, and Sycamore.31

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries the Jordan was, as it is today, prone to destructive flooding. On August 14th, 1868, an ‘extraordinary rain-fall’ caused the creek to overflow its banks for the first time since 1850. ‘Many families living along on the bottom were driven to the second story of their houses. The foundry of Holcomb & Thompson was injured to the extent of several hundred dollars, and Allen, Mitchell & Co.'s mill was greatly damaged.’32 In June of 1875 even greater damage was done:

‘OLD PROBS. He sends us quite this shower, thank you—water overflowing Boonville Steet—sweeping everything. Little did our peaceful city, quietly slumbering amid the enormous fields of growing grain that surrounded it, expect to see the flood which fell upon us on Friday night. Old Probs had warned us of approaching waters, telling us that upon that day would be visited upon our heads a soaking wet—such as we had never seen before. But few who read the probabilities of that morning believe in ghosts, or editor’s jokes. Hence, no preparations were made: and the little dark cloud which hovered over the city at noon found none to admire or fear. […] Soon after dark the rain began to fall and continued steadily until eight o’clock the next day.[…] Everyone's cellar was full, everybody's kitchen that came near being so. At this time Jordan left its banks, and within an hour was sweeping off cabins, swimming horses, and playing the deuce generally. At seven o’clock citizens passed on dry ground, at eight the water went raging down Mill Street, as if it were a tail-race.’

A new building construction was torn from its foundation, some Black residents of the low-lying properties had to be rescued with rope, and a baker had to carry his family out of their house on his back, while those with upper floors observed the drama.

‘The iron works blew its whistle as usual, and the workmen took their places. Within a half hour the boys were floating head foremost down Mill Street. They left the hammer and the saw, and ‘saw’ the hammer and the anvil no more that day. The water flooded into their furnace, and shut off their steam before they were aware of the situation. In their office the water stood about a foot deep. […] Driftwood floating down the stream in a measure checked the force of water in the channel, backing it up till it overflowed the lowlands east of Boonville Street. This no doubt saved the Wagon Factory from utter demolition. As it was, the building and engine room was flooded. A good deal of manufactured stuff was washed away, and a good deal more of mud left in its place. […] J. G. Raither, lumber dealer, probably lost as much as anyone in the city. The flood swept down upon him unawares, shoving his lumber out of his yard, as if it were straw, and whirling it along with great rapidity. […] the entire sidewalk from Boonville St. to Campbell St. was swept away. The sidewalk and stone curbing on West side of Boonville St. was washed out, besides much damage on the east side of the street. […]’33

In the following year, more flash flooding arrived:

‘Yesterday morning at four o’clock it commenced to rain so violently and persistently that people thought the heavens were breaking […] the repeated washouts of streets and washaways of whole sidewalks, however, will in course of time make too much economy equivalent to extravagance [….] The culverts that have been built do very well in dry weather, but the water passes by and over when it rains like it did yesterday. Wagon-loads of earth which it took days to remove to the highways are swept down the Jordan in a second. […] This is the third time within a year that the Jordan has transgressed its righteous boundaries. We do not know of any Egyptians drowned, but the faithful taxpayers of the valley have a claim upon our city for protection of property and life which ought not to be disregarded.’ 34

In 1883 flooding was worse upstream, but knocked out some of the less robust bridges downtown. The temperamental water level of Jordan Creek was exacerbated by the early industrialists, as in 1882 when the owner of the lumberyard land at Main down a few blocks from the Wagon Company, W. L. McLaughlin, had diverted water, reducing current that the wagon company had been using and caused some flooding on the Wagon Company’s lumber yard. The resulting lawsuit caused McLaughlin to remove the dam, but in December he built a stone wall across the creek, causing another flood, followed by another lawsuit brought by the Wagon Company, and he again had to remove the structure.35

The Railroad Arrrives and the Wagon Company Moves On

In 1878 the railroad came to downtown with the Springfield and Western Missouri Railroad Company (soon reorganized and known as the Missouri River, Fort Scott & Gulf Railroad) and a large two-story depot at the corner of Mill and Main Streets. While the depot that had established North Springfield—until 1887 a separate and rival sister city along Commercial Avenue (aka North Town or Moon City)—had been in operation since 1870 (the history of the various rail companies in Springfield is too complex to describe here), ‘This was the first railroad track ever laid within the limits of Springfield, and the first road that could really be claimed by this city’:

‘It is not strange that more than an ordinary degree of interest was felt by the citizens in the laying of the last few rails which should connect the city with the great network of railroads of the country. About 3 P. M., on the 20th day of May, 1878, the people of Springfield were startled by the prolonged whistling of the engines in the Wagon Factory and the Iron Works, and by the ringing of the alarm bell in the Bell Tower in the center of the public square. Nearly all at first thought it was a fire alarm, but in a few moments word was passed from one to another that it was the signal announcing the approach of the first regular train on the Springfield & Western Missouri Railroad. This discovery, however, did not check, but rather added to the excitement which prevailed upon the streets, and hundreds of people—men, women and children, white and black, old and young were seen hastening toward the depot, or gathering in groups along the brow of the hill which commands a view of the track. When the whistles began to blow in town, they were answered by the shrill whistle of the Thomas A. Scott, the locomotive which was bringing in the train, and a halt was made near the bridge over Wilson Creek, to give the crowd sufficient time to secure suitable places of observation. Four or five hundred of the more eager and enthusiastic "citizens and small boys" went up the road to meet and welcome the train.’36

The Frisco would take over this route in 1901, and the depot was expanded in the 1920s (the popular Harvey House restaurant was located in the terminal on the east side). Passenger service continued up until 1967, and the structure was demolished in 1977.

-

Rail Depot on Mill Street, 1890

Image courtesy of the Springfield-Greene County Library District Louis Griesemer Collection

-

New Rail Depot, photographed 1947

Passenger depot in front (demolished 1977), freight depot behind it; with view of downtown. Image courtesy of the Springfield-Greene County Library District Louis Griesemer Collection

-

New Depot, photographed 1947

Passenger depot down Mill St (note Electric Co, and Brick 1 building visible at far right in distance). Image courtesy of the Springfield-Greene County Library District Louis Griesemer Collection

-

Freight Depot constructed over Jordan Creek

Photo ca. 1940. Image courtesy of the Springfield-Greene County Library District Louis Griesemer Collection

At the same time that the railway arrived, a new iron bridge for Boonville was finally on its way.

'Twelve years ago Boonville street pitched abruptly from the square to the center of the bed of the Jordan, which was crossed by a foot plank. The growing importance of the street as a commercial highway forced itself upon the city government until by repeated spasmodic efforts, chasm which virtually separated the northern from the southern portion of the city, was filled some 12 or 15 feet in the present wooden bridge constructed. This answered the purpose for a number of years until the structure began to rot, and reel to and fro, rendering it an eyesore and dangerous to life and limb.’37

At this time in 1879, the first streetcar route—drawn by horses and run by the Springfield Traction Company—began operation along Boonville, connecting the city square to Commerical Street, linking the north and south city centers and their rail depots.

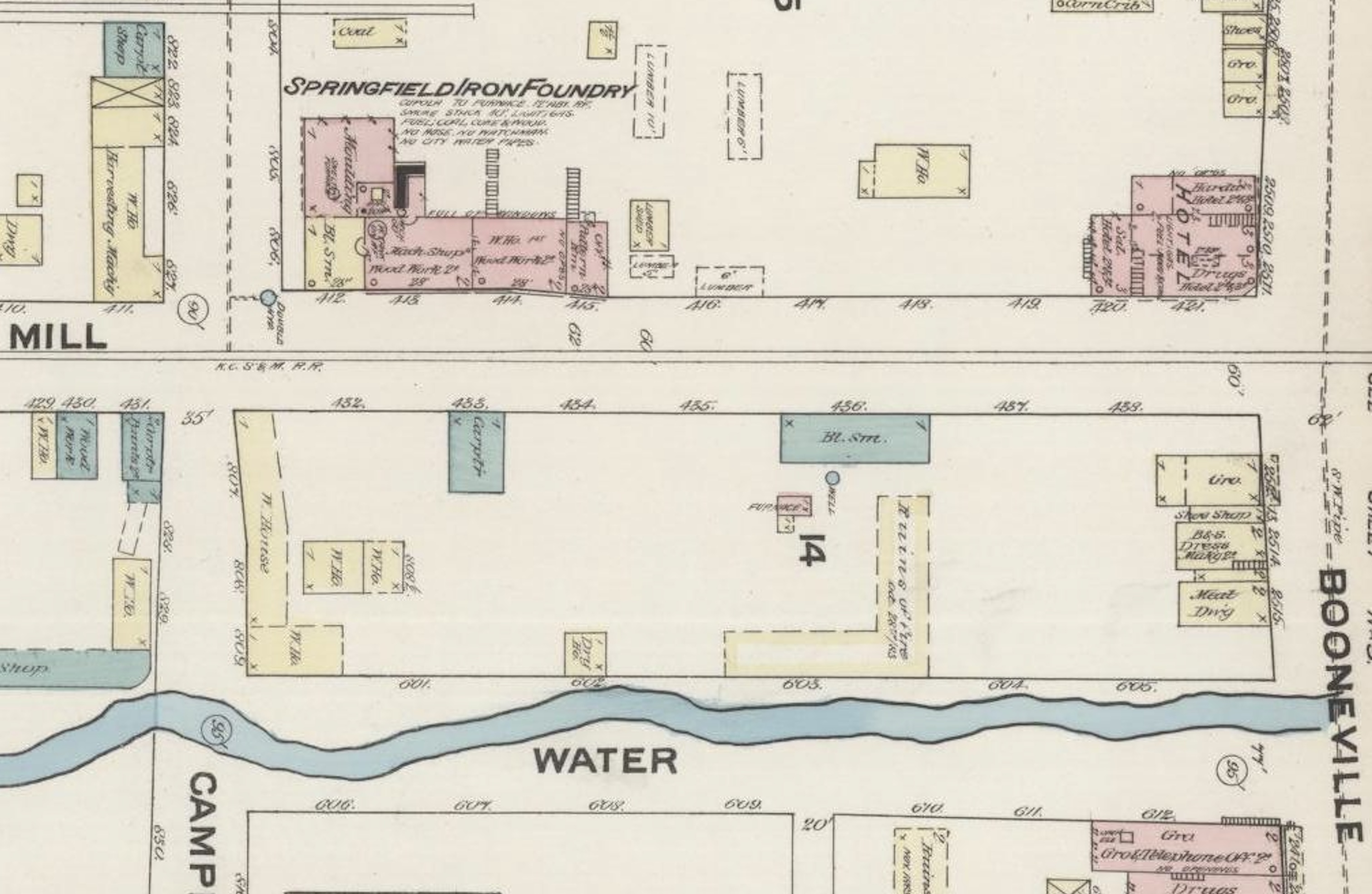

The Springfield Wagon Company both spurred much of this activity and profited from it; its production capacity doubled by May 1883, building 250 wagons a month, with innovative features including steel tires. The story of the Wagon Company as it related to Mill and Boonville is, however, a relatively short one, as on the morning of Oct. 28 1883 a fire that started in a defective drying kiln left the site in ruins by the next morning. This resulted in a loss of 25 thousand dollars in structures, machinery, and materials—only a stock of finished wagons survived—to a total of $45,000 against under $20,000 held in insurance.38 The potential profit remained clear, though, and after deliberation and bids by various towns, the company was given some land and cash by the city of Springfield to build again at Jordan Creek but some distance further upstream at Sherman and Chestnut at a junction of the two railways (now the location of Harry Cooper Supply) before an ultimate departure for Arkansas.39 Archaeology in recent decades has verified both the location of the Wagon Company and the relative vacancy of the site ever since the fire.40 In the first Sanborn Insurance Company map of Springfield, produced in the following year, only the remains of the fire are marked where the Wagon Company once stood.

Industry and Commerce at the Turn of the Century

The other commercial activity along Boonville and Mill, however, remained strong: between Mill and Olive, where today there are only parking lots and the still-standing Gottfried Furniture building of 1890—now Carolla Gallery—the Sanborn maps and commercial registries of the 1880s and 1890s indicate blocks filled with brick buildings active with business: artists, artisans, and manufacturers like shoemakers, saddle-makers, marble-sculptors, photographers, blacksmiths, carpenters, millers, bakers, confectioners, carriage-makers, dress-makers and seamstresses, bookbinders, and cabinet- and furniture-makers; and also merchants and services like grocers, butchers, barbers, hotels, cigar-dealers, pharmacists, stables, plumbers, physicians, attorneys, and the first newspaper office of the Springfield Leader /Daily Leader. The 300-block of Boonville south of Carolla featured the stately 1880s Headley Block of storefronts, and the St James Hotel had moved to 403 Boonville by 1888, in which a saloon was opened that year.41 On the east side of Boonville between Mill and Phelps, the company of S. A. Brown & Co. Lumber set up shop in 1881 carrying a wide array of building materials, the Central Hotel was operating at the northwest corner of Mill and Boonville, and off Phelps Street on this block the Electric Light Works had been established by 1886 (that location is now somewhere in the parking lot west of Obelisk Studios), in the following years moving somewhat west along Phelps to the southeast corner of Main.42 By 1896 that location was occupied by a large structure housing the Springfield Ice and Refrigerating Company and the Anheuser Busch Brewing Association. Campbell Street by this time finally crosses the Jordan with a stone arched bridge.

The Springfield Foundry and Machinery Company would remain active at the location of Brick 1 until 1901, when the owner at the time sold the structure, which was emptied of its machinery and torn down. A lawsuit filed by the Foundry owners demanding back rent or possession in 1902, however, claimed that the Springfield Ice and Refrigerating Company had taken possession of the corner property in mid-May of 1901 and was essentially squatting on it; after the foundry buildings had been torn down, a tall picket fence had been erected around it and it was currently being used to house chickens and ducks; ‘It has been expected that the Busch company would finally obtain possession of the entire block in which the property is located.’43 This did not come to pass; the suit continued into the following year.44 Some handover occurred and from 1908-10 on the site the Springfield Coal and Material Company had its offices, selling various sorts of coal, sand, cement, etc. At the turn of the century Hummel Lumber Company had a yard across Mill Street, and a wholesale produce and poultry store stood on Campbell between Mill and the creek; in 1909 the Springfield Hide and Junk Company incorporated, visible on the 1910 Sanborn map on that site.

-

Boonville Street looking north from Water Street

1920s. Springfield Public Transportation Photo collection, History Museum on the Square.

-

Boonville Street looking south from Water Street.

Note Gottfried's Furniture at left, now the home of Carolla Gallery. 1920s. Springfield Public Transportation Photo collection, History Museum on the Square.

-

Boonville south, 2024

-

Corner of Boonville and Mill

Replacing streetcar tracks: Looking down Mill to west, Springfield Ice and Refrig. cold storage (Brick 3) background left, Central Hotel right. 1915.

-

Boonville and Main in 2024

Boonville and Main in 2024

CONTINUE TO PART 2: THE TWENTIETH CENTURY

[1] A. Holly Jones, Gina Powell, Dustin Thompson, and David Quick, Jordan Creek: History, Architectural History, and Archaeology: Center for Archaeological History Report No. 1277 (Jan. 2007), 12–13, 15.

[2] Jones, et al., 12–15.; https://thelibrary.org/lochist/historicalsites/2.cfm; https://ozarkscivilwar.org/archives/1503

[3] Springfield News Leader (9/26/1954), 39; R. I. Holcombe, History of Greene County, Missouri (St. Louis: Western Historical Company, 1883), 183.

[4] Katherine Lederer, Many Thousands Gone: Springfield’s Lost Black History, 12; Richard Lee Burton, “Benton Avenue A.M.E. Church,” National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 2001); Jones, et al., 44.

[5] Loring Bullard, Jordan Creek: Story of an Urban Stream (Springfield: Watershed Committee of the Ozarks, 2001), 3.

[6] Springfield Weekly Patriot (6/8/1865), 3. This structure, however, was torched by an arsonist in 1865: as the Springfield Weekly Patriot reported, the church building, which had also been used as a school for the previous few years, ‘and the fire is said to be the work on an incendiary.’

[7] The Cumberland Presbyterian Church before the Civil War met as a mixed congregation at a church on National, and 1859-69 built a frame structure at Jefferson and Olive, the Second Cumberland Presbyterian Church, established as a newly-segregated congregation in 1865. By 1872 they were meeting at a frame building on the southwest corner of Water and Benton, and for a time the Second Baptist church was permitted to also use this building for their separate services. An African Methodist Episcopal Church was organized after 1874 with a schism in Wilson's Creek Chapel; this group for some time rented and met in an old brewery on Water Street north of the Square before finding more permanent accommodations west of the Square. Lederer, 28–31; Burton.

[8] Court records were rediscovered in 2017 by Connie Yen, the director of the Greene County Archives; https://www.ozarksfirst.com/news/news-leader-special-report-the-milly-sawyers-story/)

[9] Jonathan Fairbanks and Clyde Edwin Tuck, Past and Present of Greene County, Missouri (1914), 663; Fragments of the early history of Springfield and Green County Missouri (Springfield, 1979), 9, 18, 59.

[10] Roscoe Conkling and Margaret Conkling, The Butterfield Overland Mail 1857-1869 (Glendale CA: Arthur H. Clark Company, 1947), 180–1.

[11] Fairbanks and Tuck, 663; Republican (5/2/1915).

[12] Personal Reminiscences… 9.

[13] Springfield Mirror (7/3/1856), 4; Springfield Mirror (1/15/1857), 4.

[14] Fairbanks and Tuck, 663–6; George S. Escott, History and Directory of Springfield and North Springfield (Springfield: Office of the Patriot-Advertiser, 1878),132; Sanborn Map Company, ‘Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps: Springfield, Missouri’, 1884.

[15] Fairbanks and Tuck, 667; Escott, 87.

[16] Jason P. Mitchell, ‘Gottfried Furniture Company,’ National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 2006); Fairbanks and Tuck, 663; Springfield Weekly Patriot (08/24/1865), 2.

[17] Holcombe, 256, 364, 391; Springfield Weekly Patriot (8/24/1865), 2; Springfield Weekly Patriot (5/3/1866), 3; Springfield Weekly Patriot (5/23/1867), 3.

[18] Springfield Weekly Patriot (2/7/1867), 2; Springfield Leader (4/12/1877), 2.

[19] Springfield Weekly Patriot (3/3/1881), 3.

[20] The Springfield Leader (11/12/1868), 3.

[21] Springfield Weekly Patriot (7/6/1871), 2.

[22] Springfield Weekly Patriot (7/30/1868), 1.

[23] Fairbanks and Tuck, 1610-13; Pictorial and Genealogical Record of Greene County, Missouri, 1893. 304-7.

[24] See Mara W. Cohen Iohannides, ‘The Community Memory of Springfield, Missouri Suppresses the City’s Jewish Past,’ in Jews and Non-Jews: Memories and Interactions from the Perspective of Cultural Studies, Lucyna Aleksandrowicz-Pedich and Jacek Partyka, eds. (Frankfurt A-M, 2005), 63–4; Springfield Weekly Patriot (8/9/1868), 2; Springfield Weekly Patriot (12/30/1869), 2.

[25] Springfield Leader and Press (7/27/1870), 4; Springfield Leader 9/15/1870, 2).

[26] Holcombe, 776; Steven Lee Stepp, The Old Reliable: The History of the Springfield Wagon Company, 1872-1952 (1972),12–14, 19.

[27] Stepp, 27–8, 35-6, 46–7; Springfield Weekly Patriot 1/3/1878, 4).

[28] Springfield Weekly Patriot (12/28/1878), 2; Springfield Weekly Patriot (11/23/1876), 3; Springfield Weekly Patriot (10/31/1878), 3; Jones, et al, 60; Springfield Weekly Patriot (5/23/1878), 3; The Springfield Leader (4/18/1889), 5.

[29] Springfield Leader and Press (8/4/1870), 4.

[30] Springfield Weekly Patriot (7/12/1877), 3; Springfield Leader (6/28/1877), 5; Springfield Weekly Patriot (8/16/1877), 3.

[31] E. S. Glover, Birds Eye View of Springfield, Missoui, 1872 (Cincinnati : Strobridge & Co. Lith, [1872]).

[32] Holcombe, 770.

[33] Springfield Weekly Patriot (7/1/1875), 3; Holcombe, 547.

[34] Springfield Leader (7/13/1876), 3.

[35] Springfield Leader (6/10/1863), 4; Stepp, 57–8.

[36] Escott, 109.

[37] Springfield Weekly Patriot (11/17/1881), 3

[38] Stepp, 59-61.

[39] Stepp, 64; Springfield Daily Herald (6/18/1884), 4.

[40] Jones, et al, 73.

[41] Springfield News-Leader (6/1/1888), 5.

[42] Fairbanks and Tuck, 701.

[43] Springfield News-Leader (3/27/1901), 8; Springfield News-Leader (3/29/1901), 5; Springfield News-Leader (10/11/1902), 6.

[44] Springfield News-Leader (1/14/1903), 5.